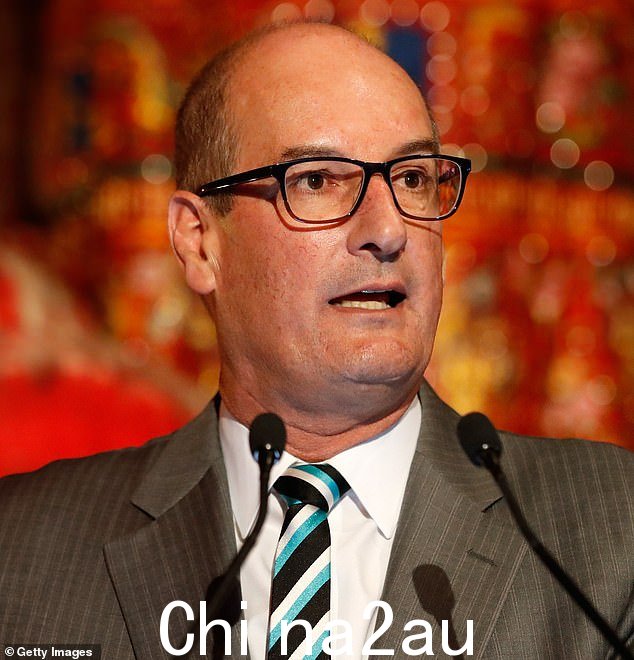

Compare the Market economic director David 'Kochie' Koch explains the complexity of the housing crisis and how we might solve it.

Back in the 90s, the average loan size in Australia was $67,000. It’s now nearly 10 times that amount at $637,000 or more if you want to live in the capitals.

But the housing crisis isn’t just about unaffordable prices - it’s about supply shortages, regulatory constraints, and the growing gap between wages and property values.

A key difference between the 90s and now is that average mortgage size has risen six times faster than wages.

So, is there a solution to our housing crisis that will keep everyone happy? Here are five things governments can do now to take heat out of the market and supply homes for the next generation.

1. Negative gearing reform

Negative gearing was introduced in 1936, in the midst of the Great Depression, to encourage investors to buy property and then rent it out to those who couldn’t afford to buy their own home.

The intention was to ease the financial burden of the large upfront and ongoing costs of buying a rental property when compared to other more traditional investments.

Now, negative gearing is ingrained in the Australian psyche. The beneficiaries aren’t just faceless behemoths, but regular mum and dad investors looking to grow wealth for their families. Without it, we could see rental stock come off the market causing costs to spiral out of control.

David 'Kochie' Koch explains the complexity of the housing crisis and how we might solve it

Getting rid of negative gearing would be controversial. But there is no doubt it needs reform because the system is being exploited.

Tax concessions should be scaled back or stopped completely. An upper limit could also be imposed to limit the number of properties which can be negatively geared by any one taxpayer.

2. Make room for medium-density

One of the most critical yet often overlooked solutions to our housing crisis is embracing medium-density housing.

When most Australians think of a home, the image that often comes to mind is a single-family house with a backyard - a Federation bungalow or a weatherboard Queenslander on a quarter-acre block. But as Australia grows, so too must our perception of what makes a home.

Medium-density housing, which includes townhouses, row homes, and low-rise apartment buildings, offers a practical solution to the supply-demand imbalance plaguing our cities. These types of developments allow for more homes to be built on less land, making it possible to house more people without sprawling further into green spaces or compromising the quality of our neighbourhoods.

3. Build where people want to live

Satellite cities on the fringes can be great but if the commute is longer than an hour, lifestyles take a major hit.

Reforming zoning regulations is crucial. Local governments often impose restrictions that limit the density and type of housing that can be built, particularly in high-demand urban areas.

By relaxing these regulations and encouraging higher-density developments in well-serviced areas, we can increase the number of available homes without encroaching on green spaces or existing infrastructure.

Be the first to commentBe one of the first to commentCommentsWhat's your take on the housing crisis?Comment now

Many young Aussies are struggling to get on the property ladder, and blame baby boomers for their housing troubles. (Stock image of young Aussies at a music festival)

4. Rethink the way homes are built

Prefabricated homes were a quick fix to plug housing supply gaps after World War II. Why can’t they be part of the solution today?

Temperature controlled facilities, where buildings can be produced safely and swiftly, free of weather delays, and the fury of the scorching Australian sun, could be a game-changer.

Read More

Why this single photo of an Australian suburb has sparked a huge debate about the future of our country

5. Do away with rubbish policies

Now here’s the controversial part: giving people more money to buy a home is not going to fix this problem. Politicians love handouts and money incentives because they are simple policies and to voters they look good on paper.

But the problem with incentives like the Homebuilder Scheme is that rather than helping bridge the gap for buyers, they simply push prices higher and further out of reach.

For example, let’s look at the Coalition’s proposal to allow buyers to raid their superannuation for a deposit. Analysis by the Super Members Council suggests such a policy would add 9% to median prices in capital cities. The extra cash isn’t all that helpful when it’s just eaten away by higher costs.

Throwing more money at the issue just isn’t the answer. We need tangible relief in the form of bricks and mortar.

Kochie calls for an end to the boomer blame game

David Koch has called for an end to the blame game where all the housing affordability woes of younger people are blamed on baby boomers.

The former Sunrise host said the attacks on his generation had become so normalised they should be called the 'scapegoats', rather than boomers.

He said this not because their 'balding heads mean we now resemble a barnyard creature, but because our lambs seem to think we've put them on the chopping block.

'Not enough houses? Boomers are hoarding them. Not enough home units? Boomers throw down cash before first-time buyers can say boo!'

Koch said contrary to popular opinion, most older Australians agree that the property market is broken and that it pains them to see their kids and grandchildren struggle.

He said those who can afford to do so, do all they can to help their children get on the housing ladder.

What's known as 'the Bank of Mum and Dad' is now, in aggregate, the sixth biggest home lender in Australia,' he wrote.

The former Sunrise host said the attacks on his generation had become so normalised they should be called the 'scapegoats', rather than boomers. Stock image

And, according to Australian Housing Monitor research, they contribute money to 40 per cent of first home buyers - a huge increase from 15 per cent in the 1980s.

Koch said it's not the boomers' fault that the real estate market that has changed drastically in recent decades.

'When we bought our homes, prices were more accessible, and while interest rates were sky-high, our wages were aligned with housing costs,' he said.

Compare the Market research, shared with Daily Mail Australia, has found the cost of buying a home in Australia's capital cities is now 14 times annual income, up from five times the annual income from 1990.

'Housing markets have inflated, wages have stagnated, and opportunities for younger generations are considerably diminished,' Koch said.

He said what has happened with housing is not about denying younger generations opportunities, but that the system has long favoured real estate as a safe investment.

While Koch said he doesn't own an investment property himself, he knows that 'the people who do are usually just regular mums and dads trying to grow wealth to support their families'.

Koch said contrary to popular opinion, most older Australians agree that the property market is broken. A house for sale is pictured

He pointed out that 'without investors, there would be nowhere to rent, and that's not a good situation either'.

Koch said that very few boomers fit 'the wealthy, elite stereotype we often see in the news'.

While some may be well off, many are middle-class people who have worked hard to achieve what they've made in life, including homeownership, he said.

'It's essential to recognise this diversity and avoid vilifying the entire generation.'

Koch also addressed the pressure being put on boomers to sell up and move to a smaller property, freeing up their houses for younger families.

But he pointed out that homes are not just assets, they also contain a lifetime of memories and moving out involves significant emotional and lifestyle adjustments.

He also said that with the average retirement age now 64, many boomers are still working, with active careers and responsibilities that require living in larger spaces.

'It's also worth noting that many older Australians hold onto their family homes because their adult children live there longer,' he said.

He said that government policy is largely to blame for the dire housing situation.

'Governments have simply not planned for either the generational housing change or the big increase in migration to ensure enough properties have been built to meet demand.'

He ended with a plea to 'stop the blame game ... rather than pointing fingers, let's focus on how we can work together to make housing more affordable in Australia'.

David Koch澳洲中文论坛热点

- 悉尼部份城铁将封闭一年,华人区受影响!只能乘巴士(组图)

- 据《逐日电讯报》报导,从明年年中开始,因为从Bankstown和Sydenham的城铁将因Metro South West革新名目而

- 联邦政客们具有多少房产?

- 据本月早些时分报导,绿党副首领、参议员Mehreen Faruqi已获准在Port Macquarie联系其房产并建造三栋投资联